It's been almost a decade since I started venturing into the life sciences sector and discovered the beauty and complexity of our biology. During this time, I've witnessed two full cycles where AI has promised transformation in drug development. The fruits of some early initiatives are just starting to pay off, while many technological claims are yet to bear tangible commercial value.

We've heard bold claims about AI reducing the cost of drug discovery to a fraction and exponentially increasing productivity—something desperately needed when examining the industry's performance. The gap between return on investment for every dollar spent on R&D keeps widening. Recent 2024 estimates suggest each drug now costs approximately $3.5 billion to develop, with timelines stubbornly remaining at the 15-year industry average.

Several challenges have led to these staggering figures—from overly complex biology to our narrow view of chemistry. The industry's eyes are now on AI to help match biology's complexity with sophisticated models and unleash chemistry's creativity with novel discovery engines that will help us imagine the impossible. Looking to AI for solutions is a trend more than a decade in the making, so let's explore what the industry has accomplished, what worked, what didn't, and where the path forward might lead.

Transforming Drug Discovery Economics

This is indeed a pivotal moment in human history. With the first AI-designed drugs entering clinical trials, we stand at a threshold where machines are poised to contribute to saving millions of lives. Drug discovery has historically been slow, costly, and extremely uncertain—primarily due to intricate complexity. Unlike physical systems, where our understanding enables precision in rocketry and aviation, we simply cannot simulate our biology with the same accuracy.

When we place medication in our bodies, we cannot precisely predict side effects or efficacy until human trials—a fundamental limitation in drug development. To compound matters, our understanding of chemistry (the primary source of medications) remains severely limited. Estimates suggest we only know the chemical structure of less than 1% of nature's chemistry, yet this tiny fraction is the source of more than half of today's marketed drugs. Aspirin and Penicillin—medications saved millions of lives and generated billions in revenue—were discovered by accident and not for their initially intended use. Imagine the possibilities when unlocking the remaining 99% of chemistry.

These factors explain why approximately 90-92% of drug candidates fail during clinical development: about 40-50% due to lack of efficacy (blocking the selected target doesn't cure the disease as hoped), approximately 30-35% due to safety/toxicity issues (engaging unintended biological targets, causing adverse events like cardiovascular problems or liver damage), and the remainder due to strategic/commercial decisions, formulation challenges, and other factors. This helps explain why drug discovery is extraordinarily expensive—we've largely exhausted known chemistry and tested these chemical entities on the biological diseases we understand. Without something truly transformative, improvements in both novel biology and chemistry become increasingly difficult.

AI Integration Across the Development Pipeline

Drug development typically spans 15 years before a medication reaches pharmacy shelves. The process begins with disease selection and identifying which pathways to target. Roughly a third of this timeline is spent discovering and developing a chemical entity that engages the target. Years follow optimizing this entity for proper administration, delivery, and engagement without causing major side effects.

Only then do preclinical studies begin, moving from in silico and in vitro testing to animal models. With regulatory approval, clinical trials commence—the notorious "death valley" where merely 5-10% of drug candidates ultimately become approved medications. Success typically means either selling the asset to pharmaceutical giants or partnering with them to navigate the enormous costs of human trials and commercialization.

AI now touches every aspect of this process. The R&D-heavy early phases particularly benefit from AI's breadth and depth. Generative AI expands our understanding of disease-causing proteins while enabling exploration of novel chemical spaces. Predictive AI enhances data interpretation, enabling faster and more efficient decision-making.

Beyond R&D, in silico simulations of cells and biological systems help predict drug reactions before testing in living organisms, reducing animal testing and increasing human trial success probability. As human trials begin, AI becomes increasingly crucial—enabling precise patient recruitment and screening. Currently, one in five clinical drug trials is discontinued not because of efficacy issues but because of inability to find suitable patient populations. LLMs can now search the internet and medical records for potentially eligible participants. AI can also screen patient samples for relevant biomarkers—biomarkers sometimes discovered by AI in the first place.

In essence, AI enables smarter prioritization, faster iteration, and better clinical translation. The efficiencies described above result from innovations developed over the past decade, and we're just beginning to see their fruition. While still at the cusp of what's possible, the future appears considerably brighter than the past. For decision-makers and investors, understanding and acting on this shift is no longer optional—it's essential.

Market Evolution: From Early Promise to Clinical Reality

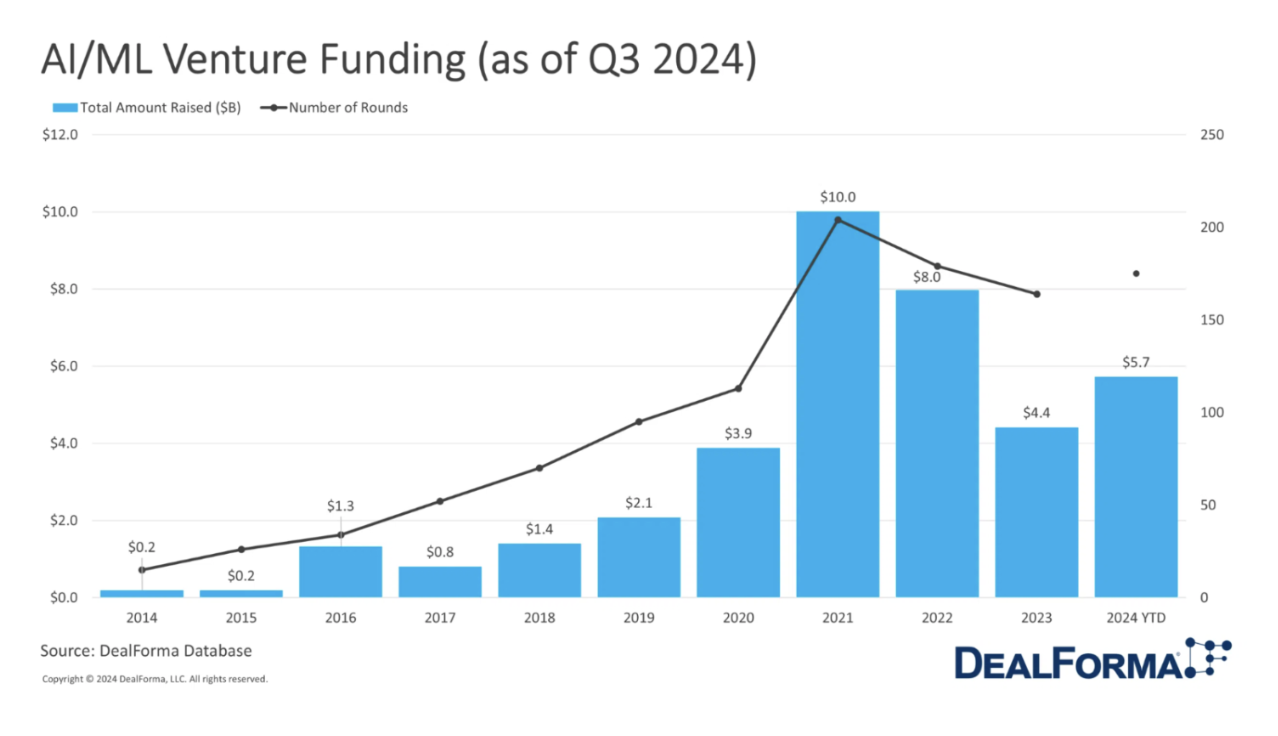

AI has operated behind the scenes in drug discovery under different identities for some time—statistical modeling, natural language processing and evolutionary algorithms have long been used to model biology and discover novel chemistry. However, AI's significant presence emerged with practical deep learning applications. Early signs appeared in 2014 with image recognition, and medical applications soon followed. Between 2016 and 2019, venture capital flooded into AI-driven startups applying various deep learning approaches to drug discovery. Atomwise applied deep learning to protein-drug interaction modeling. BenevolentAI and Healx used AI to mine literature for new biology and drug repurposing. Meanwhile, Insilico Medicine, Insitro, and Recursion utilized various AI models (computer vision, LLMs, reinforcement learning) to discover novel biology and chemistry.

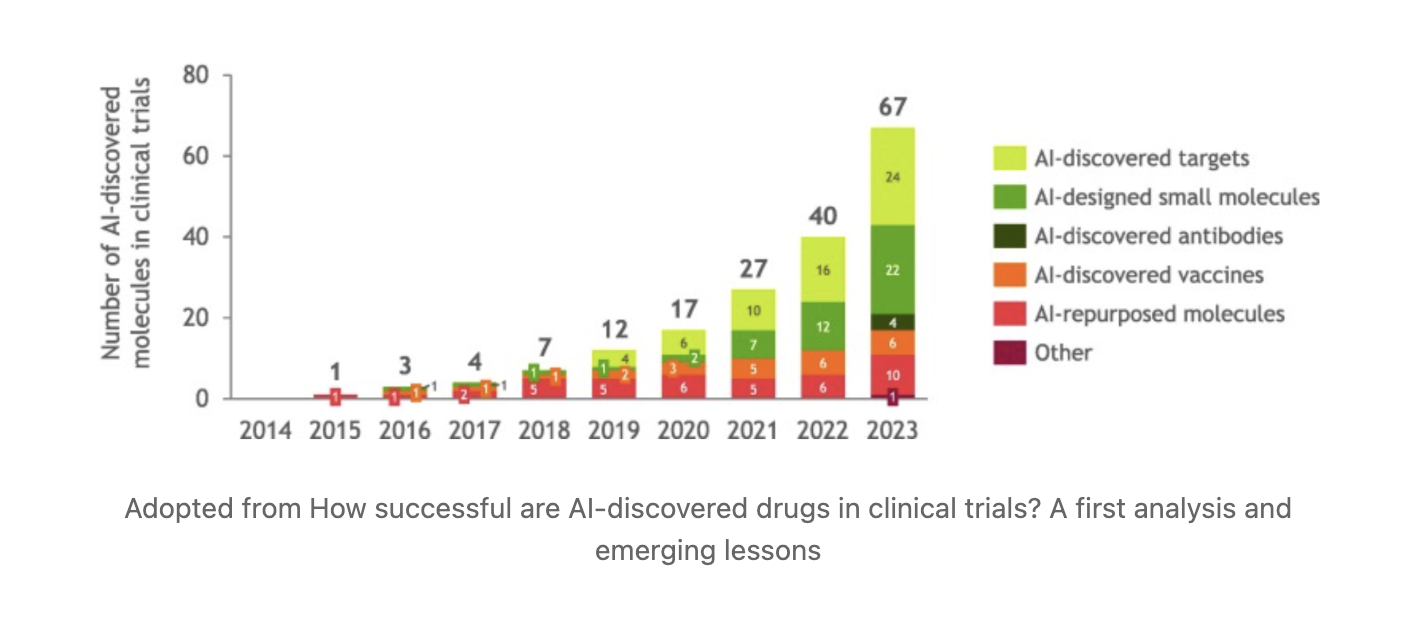

I launched my first venture in 2017 when the field seemed poised for transformation. By 2020, the first AI-designed drug candidates entered clinical trials, and by early 2024, 75 clinical assets, where AI played some role, were reported in various clinical trial phases, with the most advanced now in Phase II. While still too early for conclusive judgment (given the notorious "death valley"), these achievements represent a pivotal industry shift in both productivity and efficiency.

The industry motto "fail early, fail fast" underscores AI's evident contribution to target selection, novel chemistry design, and accelerated progression to clinical candidates—significantly reducing time and costs. This not only helps develop medicines faster but also enables larger budget allocations for innovation, ensuring accelerated scientific discovery—the holy grail for saving lives.

AI-designed drugs entering clinical trials represents a major achievement, but it's not the only measure of transformation. A subtler yet equally important impact lies in optimizing intermediate steps: virtual screening of billion-compound libraries, hit expansion, lead prioritization, synthesis planning, and improved testing in animal and human models. These efficiencies—central to my previous company, Glamorous AI—have dramatically reduced costs and accelerated timelines. A decade ago, we discussed AI's potential; today, we measure its tangible results.

Critical Success Factors and Implementation Challenges

One well-documented hurdle is data quality and availability. AI thrives on high-quality, diverse, well-labeled datasets—yet public data remains limited, biased, and often skewed toward positive results, with negative data underreported. At Glamorous AI, we developed models that could extract valuable insights even from sparse, noisy datasets—like DNA-encoded library screens—demonstrating that negative data, when effectively mined, holds substantial value.

I previously believed large pharmaceutical companies held an unfair advantage due to their vast data repositories. I've since realized that data collection conditions, consistency, and diversity matter more than mere access—creating datasets where AI can capture meaningful signals is the true challenge. With drug/cell response or disease state tissue images, for instance, AI can be easily misled by lighting conditions, dust levels, or scanner variations, challenges we are currently fixing at SpatialX. Data analytics and integration skills are chronically underrated yet critical for accurate, scalable solutions.

Data ownership and access present another challenge. Healthcare data remains highly fragmented, even within organizations. Achieving personalized therapies requires cohesively following the patient journey, including vital data (from wearables), healthcare records (from hospitals), genetic profiles (from various service providers), disease risk assessments (from family history), personal disease phenotypes (from clinical trials), multi-omics and microbiome data and population repository connections.

Some data exists in silos, while other sources are just emerging. AI must learn from individual modalities while extracting value from multimodal approaches combining signals from multiple sources (e.g., tissue imaging with spatial omics). These areas are in early exploration, and data availability remains crucial for progress.

Equally critical are human factors: adoption and culture. Like all transformational technologies, AI demands new skills and mindset shifts. Resistance often comes from expected adopters. Scaling AI across large organizations requires intentional culture change and decisive leadership.

The cultural divide between AI engineers, chemists, and biologists presents another challenge. Without "multilingual" talent—individuals fluent in multiple disciplines—effective tool integration becomes nearly impossible. This explains why many breakthroughs emerge from startups with multidisciplinary teams built from scratch—teams that would often be outliers in traditional pharmaceutical environments.

Commercial Models and Investment Landscape

Drug discovery continues to spark debate about sustainable business models. The past decade has demonstrated that no single approach guarantees success, though some models show greater promise than others—subject to change as the AI drug discovery field matures. Examples of both success and failure exist across categories, raising persistent questions: Is value rooted in the drug asset itself, or can the platform provide a sustainable path to profitability? When should companies partner, and when should they proceed independently?

Take Schrödinger as an example. The company operates primarily as a SaaS model focused on simulation and chemistry tools while recently venturing into the asset space—now investing a substantial portion of R&D budget into their spinout asset model according to recent filings. Investors appear to favor this approach, gaining both the security and predictability of SaaS alongside significant upside potential from asset development. Notably, Nimbus alone generated $147 million for Schrödinger—impressive for a company with $160 million in software business revenue that same year.

Atomwise initially opted for asset-based partnership models built on platform offerings but recently shifted to a full asset portfolio model—with outcomes still unclear. BenevolentAI operated a platform model leading to early big pharma collaborations that proved insufficient for long-term success, as evidenced by recent share price performance. Iktos maintains a platform model focused on chemistry services and continues operations. Larger players from the first generation of AI drug discovery companies—Insitro, Insilico Medicine, and Recursion—are performing well with hybrid models combining partnerships with portfolio ownership. Newer companies like Isomorphic Labs appear to follow similar trends, forming early partnerships while enhancing core technologies.

I believe both asset-centric and platform-centric approaches remain viable while AI continues rapid evolution. This allows larger players to access technological innovation at relatively low cost while enabling startups to survive through technology development and commercialization. Ultimately, drug assets represent the holy grail of value, and technological innovations must demonstrably contribute to faster/better/cheaper drugs to earn proper recognition.

Another anticipated but unrealized trend is the transformation of Contract Research Organizations (CROs). Large CROs already perform significant portions of drug development—from chemistry services to clinical trial management. It's conceivable that future AI-native CROs—with agents and robots handling much of the workload—will redefine cost structures and timelines. Such models will require substantial upfront investment but could generate significant returns by drastically reducing R&D costs and timelines—potentially rendering traditional CRO models obsolete. This transformation is beginning as AI-native drug discovery companies build labs with automation and efficiency as foundational principles, while robotics-native companies gradually enter the drug discovery space—suggesting potential convergence in coming years.

Strategic Outlook: The Next Decade

The AI-driven drug discovery market is projected to exceed $10 billion by 2030. Platform technologies streamlining and optimizing R&D will lead this growth. Early movers—those with robust pipelines, hybrid teams, and operational wet-lab infrastructure—will shape pharma's digital future and redefine benchmarks for speed, cost, and success in drug development.

Drug development remains extraordinarily challenging. Success in AI-enabled drug discovery depends not merely on technology or funding but on business model discipline, team composition, scientific clarity, timing, and substantial luck. The pharmaceutical industry invested $150 billion in acquisitions during 2023, none directed toward AI platforms. This pattern may shift as AI demonstrates utility in specific applications, particularly as co-pilot technologies or autonomously in the new era of agentic AI. Tools for synthetic route planning and chemistry co-design already show value, suggesting a future where these capabilities become essential for relevant chemists—analogous to Photoshop for designers.

Chemistry foundation models, autonomous labs, generative biology and chemistry, and integration of AI with robotics, synthetic biology, and quantum computing will define the next decade. These tools will support more efficient medicine discovery and shift from "one-size-fits-all" disease management to truly individualized therapies—treatments tailored to specific genetic, environmental, and lifestyle profiles.

Autonomous labs enabling high-throughput, low-cost experimental cycles will become mainstream as companies increasingly employ precise robots to build massive datasets for AI. AI will function as a real-time decision engine within these labs—prioritizing promising experiments, designing optimal workflows, and adapting strategies dynamically. Many components of this workflow already exist in AI-native companies, with further integration inevitable.

Meanwhile, AI will continue learning from nature as a rich source of chemistry and biology, with synthetic biology enabling fabrication of AI designs. The integration of design (AI), build (robotics), test (automation), and learn (machine learning) in iterative cycles mirrors engineering discipline—bringing industrial reproducibility and predictability to biology.

Quantum computing, though still nascent, promises step-change improvements in computational chemistry and molecular simulation. Further development of this technology for chemistry and materials design represents its most promising application.

We must maintain appropriate expectations, considering our limited understanding of chemistry and biology and the generally slow pace of regulatory advancement. Today's progress represents a decade of development. We should anticipate accelerations and efficiency gains while exercising patience and committing to long-term investment. AI undoubtedly represents drug discovery's new frontier—the only current tool approaching biology's complexity, at least until quantum computing matures. Investment in this technology will yield returns provided stakeholders appreciate its potential, effective multidisciplinary teams advance the field, and proper benchmarks and data access fuel innovation.